Hello, all. Well, I've been a bit remiss since I got back from SNARL: catching up with people, adjusting to the disgusting heat here, etc. But I like blogging too much, and if anyone reads this, I owe them the usual regimented posting pattern I've adhered to since picking up blogging. So, let me begin by regaling you with my trip, the long two-week Odyssey to Davis and halfway back...

First off, orientation. I left for Davis on August first more than a little stressed out, I must admit. My IB scores were missing, I couldn't figure out some code they needed me to have, and I was worried about both my score on the math placement exam and taking the chem exam. So, I piled groggily into the car early that morning with my dad and headed up there. And, perhaps to my surprise, the whole affair turned out to be pretty nice.

I won't go through the whole process with you, nor do I want to type it out, but basically I spent three days doing a variety of things. Firstly, and most importantly, our orientation leaders familiarized us with the class catalog and how registration works beforehand, and how to line up major and GE courses we wanted. Secondly, it gave me the chance to meet some new people. Within my major (Evolution, Ecology, and Biodiversity, one of seven for the College of BioSci, which had three ~500 person orientations), there were only seven people, and I got to know all of them personally, which was kind of cool. One guy reminded me, if I may be so bold, of myself, and I really liked talking to him. We also got to see the campus, and get our placement exams squared away (I passed both of mine, but chem was full when I registered, so I'm only taking Calculus this quarter). All in all, it was a busy, but worthwhile three days, and I'm glad to be al registered. Here's my schedule:

--Math 17A, Calc. for Biology

--Geology 1, The Earth

--Wildlife Ecology and Conservation

--And a freshman seminar on electrical issues...it was the last out of like 50 open...

After Davis though, my Dad didn't take me home. Instead, he drove me up through the mountains and down into the Eastern Sierra and dropped me off for my first official employment at the Sierra Nevada Aquatic Research Laboratory, or SNARL.

My job there consisted essentially of what I've been volunteering to do for the past few summers, by helping with squirrel research up in Rock Creek Canyon. I did that back in June, but because one of the other employees had to leave early, the professor running the study was nice enough to offer me an 11-day job up there. When I got there, it was me and one other employee in the cabin, she was also doing squirrel work, and we'd ride to Rock Creek every day with Andy, the phd student who's finishing up the study for the summer (The professor left in July, so it was just Andy, Page, and Me, and then Page left a few days after I got there).

Daily work consisted of trapping squirrels and processing them: weighing them, getting fecal samples, noting sex and age, etc.

Then, if Andy hadn't caught the squirrel recently or at all, he'd put it through a brief behavior test of curiosity called the holeboard, which examines how many holes the squirrel investigates in a set amount of time. Behavior observations, and thus dye-marking, were already done for the season. Back at SNARL, we also had a few sets of captive squirrels in the lab, and Andy would test them in a more elaborate version of the holeboard which examined their reluctance to emerge from an artificial burrow system after a predator is sighted (in this case, a Frisbee thrown over the holeboard). We also did some tests with hormone blockers, so I had to get up a couple mornings and clean the cages (we traded off), and in addition, feed the squirrels drugged peanut butter.

As for daily life at SNARL, I'll admit, at first it was a bit hard to adjust to. After Page left, I had Q8, my cabin, all to myself, and with work finishing at about noon each day, it got pretty lonely...

Ok, not

that lonely, but it was a bit depressing at times. I missed people, and it was dark as hell up there and creepy at night. But I got used to it, my mom came to visit one weekend, and I rented some movies to watch. And, the thursday before I left, I got a whole slew of roommates from UCSB doing amphibian research, and they were really nice. One was even a doppleganger for Sheldon, from "The Big Bang Theory". And I must say, do biologists ever like to

drink. I didn't know what a prairie fire was before I went to SNARL, until I watched them do one with tequila and hot sauce. I did not partake...but it was interesting to watch.

In short, SNARL was a good experience in solitude, field research, and meeting new people, all useful things for college if I may tack on a life lesson here. It was a good two weeks, and I hope you enjoyed hearing my paraphrased version of it here on my blog.

In other news:

Back in palmdale for the past week, it has been pretty fun as well.

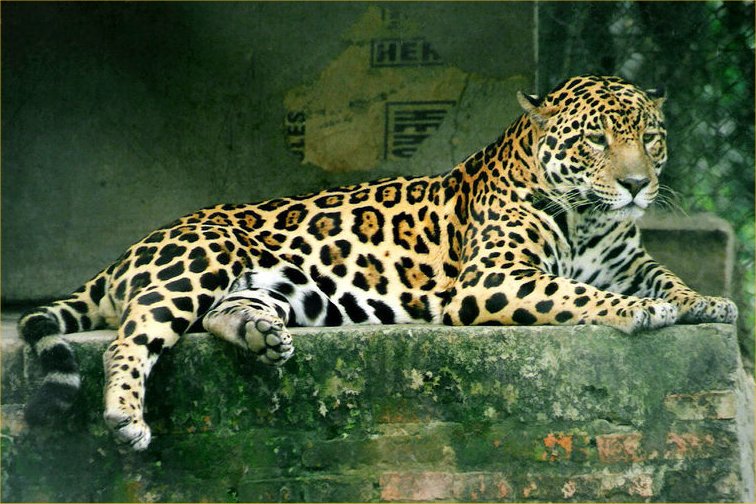

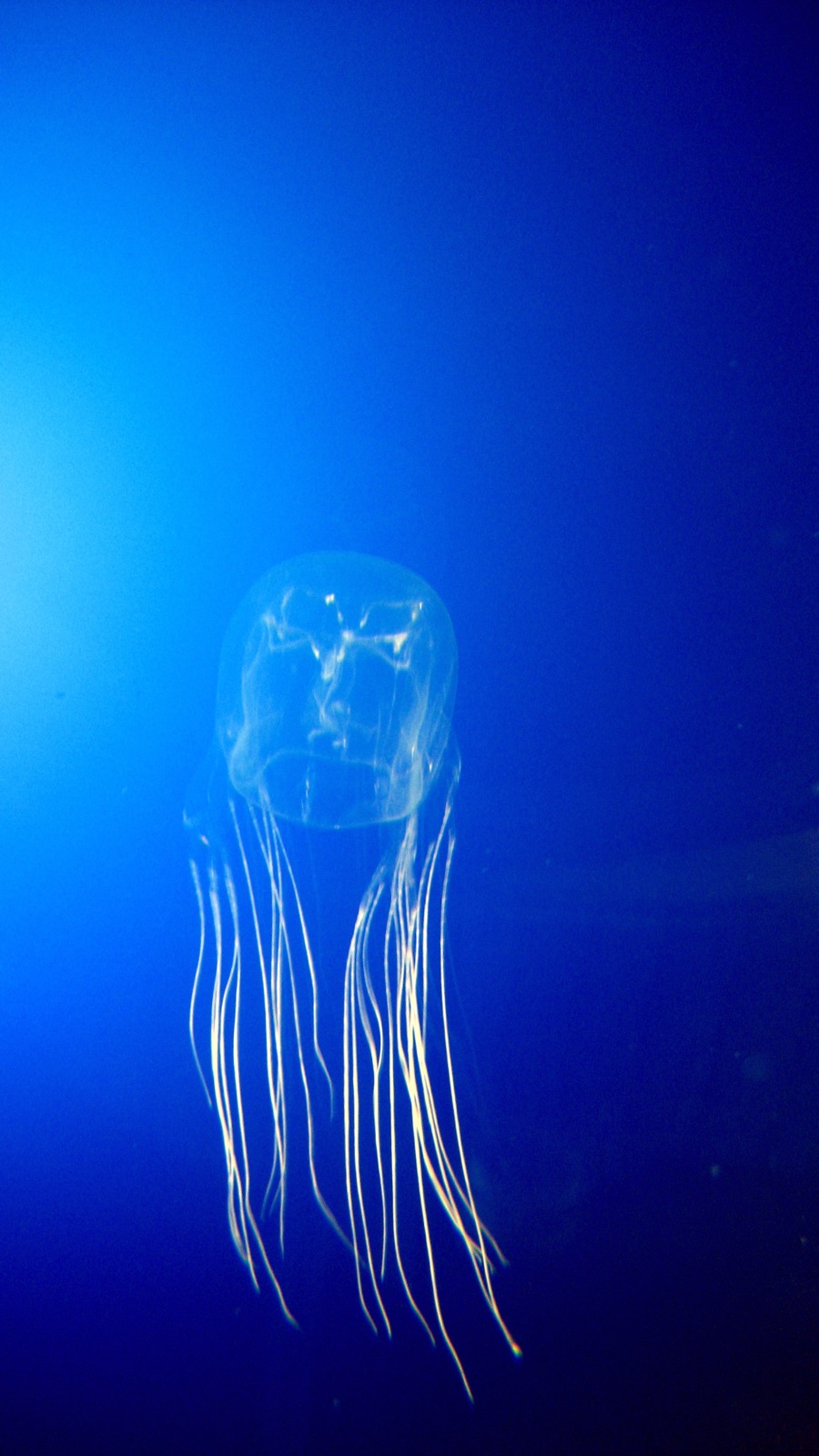

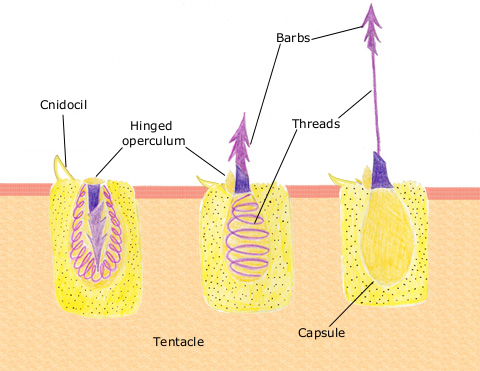

I went to the beach at Point Dume last Tuesday, and was witness to both how freezing the Pacific is even in August and a variety of sealife: purple-striped jellyfish, dolphins, and several species of birds. I also went to Magic Mountain last Friday, which was short on wildlife, but still pretty fun (I got a picture with

Batman =D). In less exciting and more nerve-wracking news, I get my wisdom teeth removed tomorrow evening. No anesthetic, only laughing gas, two are impacted...it's gonna be a long weekend...

So, that's my recap, thanks for reading: fun facts and more will resume shortly.

the curve saves me, and if not, I'll retake the course next quarter. It's not fun, and I'm really embarrassed to truly fail at a class, something I've never done before, but that's life. If I want to be a zoologist, I just have to tough it out and keep fighting Newton's challenging legacy tooth and nail...

the curve saves me, and if not, I'll retake the course next quarter. It's not fun, and I'm really embarrassed to truly fail at a class, something I've never done before, but that's life. If I want to be a zoologist, I just have to tough it out and keep fighting Newton's challenging legacy tooth and nail...