Saturday, July 31, 2010

Hello All

Sorry it's been so long since my last post, Bass Lake and this past week have been busy full of studying and fun, inversely. At any rate, I'm off to UC Davis tomorrow for my three day orientation! It should be fun at the same time that it is stressful (chemistry test and potentially a math test...joy, explains the studying I've been doing). And after that, I head straight to SNARL to start my job as a squirrel researcher! So, I'll be back on the 15th of August. I won;t have internet or time at Davis, but I may have it in SNARL, and if I do, expect from me a steady stream of fun facts to make up for it. Have a nice evening, I'll post when I can!

Monday, July 19, 2010

Fun Fact of the Day 7/19

Well, due once again to my proximity a lake, I'll share another freshwater fun fact with you all this evening. I was playing "Crush The Castle 2" earlier today, and later on in the fantastic flash adventure that comprises that game, one of the fling-able weapons given to the player by a wizard is a jar of electric eels, used to elctrocute targets inside the castle walls via metal parts of the structure.  As morbidly joyous of an experience as shocking enemies until they explode into little crimson showers was, the biologist inside of me did detect an error: electric eels can't generate anywhere near that much electricity. So that got me thinking: I should inform my readership about these animals for my fun fact today. And here I am.

As morbidly joyous of an experience as shocking enemies until they explode into little crimson showers was, the biologist inside of me did detect an error: electric eels can't generate anywhere near that much electricity. So that got me thinking: I should inform my readership about these animals for my fun fact today. And here I am.

Electric eels, despite their misleading name, are actually not eels at all. Actual eels belong to the order Anguilliformes, and this order includes such well-known species as the moray eel, and the enormous Atlantic conger eels. Electric eels, however, are closer related to catfish and carp than to true eels. Specifically, they belong to the family Gymnotidae, or the naked-backed knifefish. Unlike many true eels, the electric eel instead dwells in the freshwater of the Amazon river, like many of it's knifefish kin. Unusually for a fish, this animal also breathes air, rising to the surface every ten minutes or so to "gulp" it, obtaining 80% of it's required oxygen in this manner. They live in still or even stagnant water, feeding on invertebrates and small fish. They also have really quite interesting breeding manners as well. During the dry season, a male electric eel will make an actual nest out of his saliva, and the female will deposit a large number of eggs into it.

Now, all these things aside, the aspect that draws many people to electric eels is their namesake: their ability to generate electricity, known as bioelectrogenesis. Such a concept may inspire some pretty far-fetched images. But, sadly (SyFy, I'm talking to you.) images of electric eels setting whole stretches of water aglow with bright bolts of sizzling electricity, shocking all in sight with steaming glory are, perhaps obviously, defunct. But nonetheless, electric eels are impressive examples of the ability to do this. Now, overall, electricity did not evolve as a weapon. Knifefish, as a group use electricity not to attack or defend, but to navigate. Minute electrical fields on either side of the animal detect interruptions, allowing it to detect the direction of prey and orient itself even in pitch black conditions. And, to some degree, the electric eel can use it's shocking ability to do this as well. There are three portions of the eel's body devoted to electrical impulse production: the main organ, the hunter's organ, and the sachs organ. All three of these areas are located in the eel's tail, which makes up around 80% of it's body in the anterior portion. All three organs are comprised on a cellular level by specialized electrical cells called electrocytes. Electrocytes are flat, disc-shaped cells, with a positive charge on one side and a negative charge on the other. On their surface, they have acetylcholine receptors. When an electrical impulse begins, it originates in the so-called "pacemaker organ", a bundle of nerve cells that controls the rate of electrical impulses by sending and receiving them. When the electric eel detects prey, or a threat, this organ sends an impulse to the electrocytes, which are stacked like the inside of a battery to produce a current. When the nerves fire, they release ACH (acetylcholine), which binds to the ACH receptors on the cell surface. This in turn causes ATP powered protein pumps to actively transport large amounts of potassium and sodium ions out of the cell, creating an electric charge. Since the cells are stacked together, each one produces a charge of about 0.15 volts, but in current form, the organs can produce larger volts. The organs can produce both low and high voltage impulses, both of which vary in intensity based on the size of the eel. High voltage impulses from large adult eels can reach voltages of up to 650 volts, and 1 ampere of energy, which is potentially enough to kill an adult human. They use these impulses to locate food, to communicate, to hunt, and to defend themselves against predators.

When an electrical impulse begins, it originates in the so-called "pacemaker organ", a bundle of nerve cells that controls the rate of electrical impulses by sending and receiving them. When the electric eel detects prey, or a threat, this organ sends an impulse to the electrocytes, which are stacked like the inside of a battery to produce a current. When the nerves fire, they release ACH (acetylcholine), which binds to the ACH receptors on the cell surface. This in turn causes ATP powered protein pumps to actively transport large amounts of potassium and sodium ions out of the cell, creating an electric charge. Since the cells are stacked together, each one produces a charge of about 0.15 volts, but in current form, the organs can produce larger volts. The organs can produce both low and high voltage impulses, both of which vary in intensity based on the size of the eel. High voltage impulses from large adult eels can reach voltages of up to 650 volts, and 1 ampere of energy, which is potentially enough to kill an adult human. They use these impulses to locate food, to communicate, to hunt, and to defend themselves against predators.

Fascinating, isn't it? I love biology...

As morbidly joyous of an experience as shocking enemies until they explode into little crimson showers was, the biologist inside of me did detect an error: electric eels can't generate anywhere near that much electricity. So that got me thinking: I should inform my readership about these animals for my fun fact today. And here I am.

As morbidly joyous of an experience as shocking enemies until they explode into little crimson showers was, the biologist inside of me did detect an error: electric eels can't generate anywhere near that much electricity. So that got me thinking: I should inform my readership about these animals for my fun fact today. And here I am.Electric eels, despite their misleading name, are actually not eels at all. Actual eels belong to the order Anguilliformes, and this order includes such well-known species as the moray eel, and the enormous Atlantic conger eels. Electric eels, however, are closer related to catfish and carp than to true eels. Specifically, they belong to the family Gymnotidae, or the naked-backed knifefish. Unlike many true eels, the electric eel instead dwells in the freshwater of the Amazon river, like many of it's knifefish kin. Unusually for a fish, this animal also breathes air, rising to the surface every ten minutes or so to "gulp" it, obtaining 80% of it's required oxygen in this manner. They live in still or even stagnant water, feeding on invertebrates and small fish. They also have really quite interesting breeding manners as well. During the dry season, a male electric eel will make an actual nest out of his saliva, and the female will deposit a large number of eggs into it.

Now, all these things aside, the aspect that draws many people to electric eels is their namesake: their ability to generate electricity, known as bioelectrogenesis. Such a concept may inspire some pretty far-fetched images. But, sadly (SyFy, I'm talking to you.) images of electric eels setting whole stretches of water aglow with bright bolts of sizzling electricity, shocking all in sight with steaming glory are, perhaps obviously, defunct. But nonetheless, electric eels are impressive examples of the ability to do this. Now, overall, electricity did not evolve as a weapon. Knifefish, as a group use electricity not to attack or defend, but to navigate. Minute electrical fields on either side of the animal detect interruptions, allowing it to detect the direction of prey and orient itself even in pitch black conditions. And, to some degree, the electric eel can use it's shocking ability to do this as well. There are three portions of the eel's body devoted to electrical impulse production: the main organ, the hunter's organ, and the sachs organ. All three of these areas are located in the eel's tail, which makes up around 80% of it's body in the anterior portion. All three organs are comprised on a cellular level by specialized electrical cells called electrocytes. Electrocytes are flat, disc-shaped cells, with a positive charge on one side and a negative charge on the other. On their surface, they have acetylcholine receptors.

When an electrical impulse begins, it originates in the so-called "pacemaker organ", a bundle of nerve cells that controls the rate of electrical impulses by sending and receiving them. When the electric eel detects prey, or a threat, this organ sends an impulse to the electrocytes, which are stacked like the inside of a battery to produce a current. When the nerves fire, they release ACH (acetylcholine), which binds to the ACH receptors on the cell surface. This in turn causes ATP powered protein pumps to actively transport large amounts of potassium and sodium ions out of the cell, creating an electric charge. Since the cells are stacked together, each one produces a charge of about 0.15 volts, but in current form, the organs can produce larger volts. The organs can produce both low and high voltage impulses, both of which vary in intensity based on the size of the eel. High voltage impulses from large adult eels can reach voltages of up to 650 volts, and 1 ampere of energy, which is potentially enough to kill an adult human. They use these impulses to locate food, to communicate, to hunt, and to defend themselves against predators.

When an electrical impulse begins, it originates in the so-called "pacemaker organ", a bundle of nerve cells that controls the rate of electrical impulses by sending and receiving them. When the electric eel detects prey, or a threat, this organ sends an impulse to the electrocytes, which are stacked like the inside of a battery to produce a current. When the nerves fire, they release ACH (acetylcholine), which binds to the ACH receptors on the cell surface. This in turn causes ATP powered protein pumps to actively transport large amounts of potassium and sodium ions out of the cell, creating an electric charge. Since the cells are stacked together, each one produces a charge of about 0.15 volts, but in current form, the organs can produce larger volts. The organs can produce both low and high voltage impulses, both of which vary in intensity based on the size of the eel. High voltage impulses from large adult eels can reach voltages of up to 650 volts, and 1 ampere of energy, which is potentially enough to kill an adult human. They use these impulses to locate food, to communicate, to hunt, and to defend themselves against predators.Fascinating, isn't it? I love biology...

Fun Fact of the Day 7/18

Well, I'm spending the next extended week next to a lake, so it seems only appropriate that I share a fun fact about a little known freshwater animal that I find quite remarkable: Himantura chaophraya, the Giant Freshwater Stingray. I first read about this particular fish last summer, and I was blown away by just how immense it was. Look at the picture! Isn't that amazing? They're found in sandy river environments across Southeast Asia, particularly in the deltas of the Mekong, Bongpakong, Tachin, Tapi, Nan, and Chao Phraya rivers. It feeds on other benthic, or bottom dwelling animals, including fish and invertebrates. These animals are remarkably elusive, and their conservation status is frighteningly uncertain. Females give live birth to one baby at a time, so their reproductive cycle is remarkably slow. In short, these stingrays are quite fascinating, and I hope more is learned about them in the future, so future fun facts can fill in some detail.

I first read about this particular fish last summer, and I was blown away by just how immense it was. Look at the picture! Isn't that amazing? They're found in sandy river environments across Southeast Asia, particularly in the deltas of the Mekong, Bongpakong, Tachin, Tapi, Nan, and Chao Phraya rivers. It feeds on other benthic, or bottom dwelling animals, including fish and invertebrates. These animals are remarkably elusive, and their conservation status is frighteningly uncertain. Females give live birth to one baby at a time, so their reproductive cycle is remarkably slow. In short, these stingrays are quite fascinating, and I hope more is learned about them in the future, so future fun facts can fill in some detail.

I first read about this particular fish last summer, and I was blown away by just how immense it was. Look at the picture! Isn't that amazing? They're found in sandy river environments across Southeast Asia, particularly in the deltas of the Mekong, Bongpakong, Tachin, Tapi, Nan, and Chao Phraya rivers. It feeds on other benthic, or bottom dwelling animals, including fish and invertebrates. These animals are remarkably elusive, and their conservation status is frighteningly uncertain. Females give live birth to one baby at a time, so their reproductive cycle is remarkably slow. In short, these stingrays are quite fascinating, and I hope more is learned about them in the future, so future fun facts can fill in some detail.

I first read about this particular fish last summer, and I was blown away by just how immense it was. Look at the picture! Isn't that amazing? They're found in sandy river environments across Southeast Asia, particularly in the deltas of the Mekong, Bongpakong, Tachin, Tapi, Nan, and Chao Phraya rivers. It feeds on other benthic, or bottom dwelling animals, including fish and invertebrates. These animals are remarkably elusive, and their conservation status is frighteningly uncertain. Females give live birth to one baby at a time, so their reproductive cycle is remarkably slow. In short, these stingrays are quite fascinating, and I hope more is learned about them in the future, so future fun facts can fill in some detail.

Saturday, July 17, 2010

Fun Fact of the Day 7/17

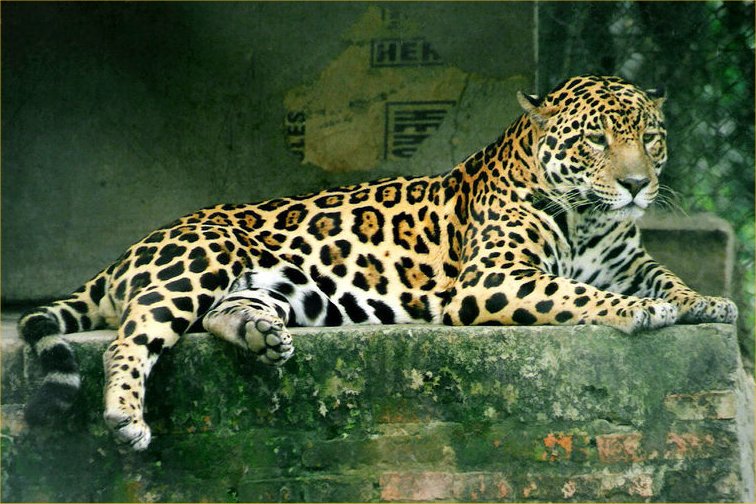

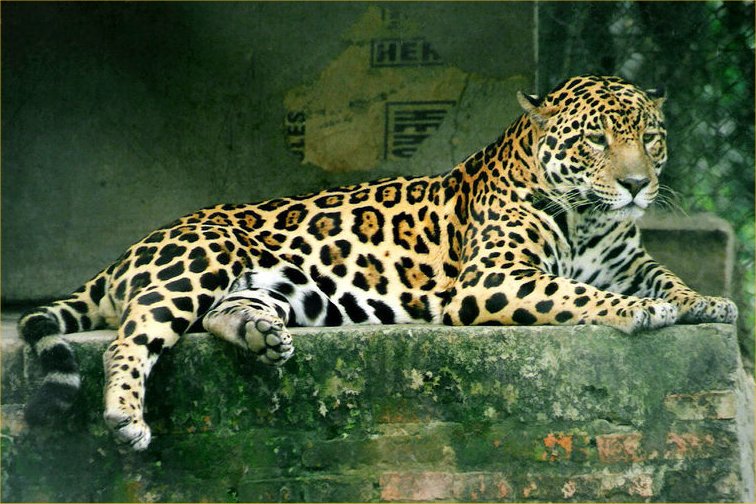

Well, I sometimes use these fun facts as a means of imparting on my limited readership aspects of zoology which many people do not notice or often mistake. In other words, I have "pet peeves", things that people often mix up or forget about certain animals. The difference between apes and monkeys, for example. Today, I'll highlight another such common misconception: the notion of a "panther". Now, first let us define what makes a panther. Basically, a panther is a big cat, one that specifically displays dark (nearly black coloration). Now, as I understand it, it is a common misconception that the panther is a species all it's own, but the real answer's a bit less impressive. Now, there is such thing as a florida panther, which a subspecies of cougar, but the black individuals in discussion here are not. In fact, "panther" as it relates to an all-black big cat is just a nickname for a particular genetic variety of two species of cats: the jaguar (Panthera onca) and the leopard (Panthera pardus).

Now, first let us define what makes a panther. Basically, a panther is a big cat, one that specifically displays dark (nearly black coloration). Now, as I understand it, it is a common misconception that the panther is a species all it's own, but the real answer's a bit less impressive. Now, there is such thing as a florida panther, which a subspecies of cougar, but the black individuals in discussion here are not. In fact, "panther" as it relates to an all-black big cat is just a nickname for a particular genetic variety of two species of cats: the jaguar (Panthera onca) and the leopard (Panthera pardus).  As most people well know, both of these cats are tan or yellow with brown and black spots covering their fur. The jaguar has larger spots, with smaller dots inside, and is found in South and Central America. The leopard has smaller spots, and is found throughout Africa, Asia, and even parts of the middle east. Now, both of these animals typically have this color pattern, but both also contain genes for melanism, which is the term for the all-black version of fur coloration. In the jaguar, this gene is recessive, and in the leopard, it is dominant. It is rare, but when expressed, it produces an all black version of the animal, thus creating a "panther".

As most people well know, both of these cats are tan or yellow with brown and black spots covering their fur. The jaguar has larger spots, with smaller dots inside, and is found in South and Central America. The leopard has smaller spots, and is found throughout Africa, Asia, and even parts of the middle east. Now, both of these animals typically have this color pattern, but both also contain genes for melanism, which is the term for the all-black version of fur coloration. In the jaguar, this gene is recessive, and in the leopard, it is dominant. It is rare, but when expressed, it produces an all black version of the animal, thus creating a "panther".  Therefore, panther is not actually a species, but rather just a black version of either a jaguar or a leopard. In fact, if one looks closely, you can actually still see spots on black jaguars and leopards, further evidence to their genetic components. So, now you know, if you, didn't before.

Therefore, panther is not actually a species, but rather just a black version of either a jaguar or a leopard. In fact, if one looks closely, you can actually still see spots on black jaguars and leopards, further evidence to their genetic components. So, now you know, if you, didn't before.

Now, first let us define what makes a panther. Basically, a panther is a big cat, one that specifically displays dark (nearly black coloration). Now, as I understand it, it is a common misconception that the panther is a species all it's own, but the real answer's a bit less impressive. Now, there is such thing as a florida panther, which a subspecies of cougar, but the black individuals in discussion here are not. In fact, "panther" as it relates to an all-black big cat is just a nickname for a particular genetic variety of two species of cats: the jaguar (Panthera onca) and the leopard (Panthera pardus).

Now, first let us define what makes a panther. Basically, a panther is a big cat, one that specifically displays dark (nearly black coloration). Now, as I understand it, it is a common misconception that the panther is a species all it's own, but the real answer's a bit less impressive. Now, there is such thing as a florida panther, which a subspecies of cougar, but the black individuals in discussion here are not. In fact, "panther" as it relates to an all-black big cat is just a nickname for a particular genetic variety of two species of cats: the jaguar (Panthera onca) and the leopard (Panthera pardus).  As most people well know, both of these cats are tan or yellow with brown and black spots covering their fur. The jaguar has larger spots, with smaller dots inside, and is found in South and Central America. The leopard has smaller spots, and is found throughout Africa, Asia, and even parts of the middle east. Now, both of these animals typically have this color pattern, but both also contain genes for melanism, which is the term for the all-black version of fur coloration. In the jaguar, this gene is recessive, and in the leopard, it is dominant. It is rare, but when expressed, it produces an all black version of the animal, thus creating a "panther".

As most people well know, both of these cats are tan or yellow with brown and black spots covering their fur. The jaguar has larger spots, with smaller dots inside, and is found in South and Central America. The leopard has smaller spots, and is found throughout Africa, Asia, and even parts of the middle east. Now, both of these animals typically have this color pattern, but both also contain genes for melanism, which is the term for the all-black version of fur coloration. In the jaguar, this gene is recessive, and in the leopard, it is dominant. It is rare, but when expressed, it produces an all black version of the animal, thus creating a "panther".  Therefore, panther is not actually a species, but rather just a black version of either a jaguar or a leopard. In fact, if one looks closely, you can actually still see spots on black jaguars and leopards, further evidence to their genetic components. So, now you know, if you, didn't before.

Therefore, panther is not actually a species, but rather just a black version of either a jaguar or a leopard. In fact, if one looks closely, you can actually still see spots on black jaguars and leopards, further evidence to their genetic components. So, now you know, if you, didn't before.

Bass Lake

Well, I'm currently in Bass Lake, CA, for a family reunion of sorts. My uncle (step-uncle if you want to be technical, but I consider him as close as an uncle) and aunt own a lake house up here, and so I'm privileged enough to enjoy swimming, boating, and excessively rough and violent inner tubing every July.  It's alot of fun, and I also get to see my cousins and extended on my dad's side every summer as well. Bass lake is man-made, a former pasture now kept submerged by a large dam at one end, so the lake is not exactly a pristine part of nature, but it does have it's natural advantages. Both Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) and a pair of Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus)

It's alot of fun, and I also get to see my cousins and extended on my dad's side every summer as well. Bass lake is man-made, a former pasture now kept submerged by a large dam at one end, so the lake is not exactly a pristine part of nature, but it does have it's natural advantages. Both Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) and a pair of Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus)  inhabit the woods around the lake, and I've seen them swoop down after fish in the water on numerous occasions. Also present around the area are raccoons, Great egrets, Great blue herons, Canada geese, Mallards, and several species of fish (including the lake's namesake, bass).

inhabit the woods around the lake, and I've seen them swoop down after fish in the water on numerous occasions. Also present around the area are raccoons, Great egrets, Great blue herons, Canada geese, Mallards, and several species of fish (including the lake's namesake, bass).  Additionally, the lake is also situated only about half an hour outside Yosemite National Park's west entrance, so it's neato for day hikes into the valley as well. All in all, I'm glad to be up here, and I'm looking forward to a pleasant week.

Additionally, the lake is also situated only about half an hour outside Yosemite National Park's west entrance, so it's neato for day hikes into the valley as well. All in all, I'm glad to be up here, and I'm looking forward to a pleasant week.

Not to worry though, I still will be posting fun facts daily ;)

It's alot of fun, and I also get to see my cousins and extended on my dad's side every summer as well. Bass lake is man-made, a former pasture now kept submerged by a large dam at one end, so the lake is not exactly a pristine part of nature, but it does have it's natural advantages. Both Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) and a pair of Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus)

It's alot of fun, and I also get to see my cousins and extended on my dad's side every summer as well. Bass lake is man-made, a former pasture now kept submerged by a large dam at one end, so the lake is not exactly a pristine part of nature, but it does have it's natural advantages. Both Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) and a pair of Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus)  inhabit the woods around the lake, and I've seen them swoop down after fish in the water on numerous occasions. Also present around the area are raccoons, Great egrets, Great blue herons, Canada geese, Mallards, and several species of fish (including the lake's namesake, bass).

inhabit the woods around the lake, and I've seen them swoop down after fish in the water on numerous occasions. Also present around the area are raccoons, Great egrets, Great blue herons, Canada geese, Mallards, and several species of fish (including the lake's namesake, bass).  Additionally, the lake is also situated only about half an hour outside Yosemite National Park's west entrance, so it's neato for day hikes into the valley as well. All in all, I'm glad to be up here, and I'm looking forward to a pleasant week.

Additionally, the lake is also situated only about half an hour outside Yosemite National Park's west entrance, so it's neato for day hikes into the valley as well. All in all, I'm glad to be up here, and I'm looking forward to a pleasant week.

Not to worry though, I still will be posting fun facts daily ;)

Friday, July 16, 2010

Fun Fact of the Day 7/16

So, a few days ago, I was at a pool party at one of my friends' houses. In addition to having a pool (which was chilly, explaining my procrastination in entering it until much later that night), she also had a sizable Koi pond in her backyard, containing around 20 of the fish.  I have always found fish fascinating. Well, hell, I find all animals fascinating, but I suppose for simple aesthetic intrigue, the fluid movements and interesting lifestyles of aquatic animals have always been a thrill to watch or learn about. Fortunately, with the koi, I had the chance to do both. Inside the house, I was looking at books on the coffee table, and I found one all about koi. Most of it was arcane stuff on their care and maintenance, with some sections even devoted to the professional showing of koi. But there was a chapter leading up to their healthcare that discussed in pleasing detail their biology and physiology. Needless to say, I read it all, and am pleased to say I now know much more about koi fish than I did before, so let me share a brief overview of the animals for my fun fact this evening.

I have always found fish fascinating. Well, hell, I find all animals fascinating, but I suppose for simple aesthetic intrigue, the fluid movements and interesting lifestyles of aquatic animals have always been a thrill to watch or learn about. Fortunately, with the koi, I had the chance to do both. Inside the house, I was looking at books on the coffee table, and I found one all about koi. Most of it was arcane stuff on their care and maintenance, with some sections even devoted to the professional showing of koi. But there was a chapter leading up to their healthcare that discussed in pleasing detail their biology and physiology. Needless to say, I read it all, and am pleased to say I now know much more about koi fish than I did before, so let me share a brief overview of the animals for my fun fact this evening.

The perhaps foremost, possibly obviously so, fact about koi is that they are not wild animals. It's impossible for one to wander off to some distant pond and find schools of koi plying the waters there, just as one wouldn't expect to find packs of golden retrievers hunting caribou in the forest. But, that being said, they are domesticated animals, and this means that they are an intriguing example of what Darwin himself drew the inspiration for his theory from: artificial selection. In this form of selection, a breeder allows only certain offspring to reproduce, those that bear the characteristics which said breeder is looking for. Instead of the most overall fit animal reproducing the most, as in natural selection (the engine of evolution), the animals bearing the most developed traits desired by the breeder are instead selected. Darwin himself did this with pigeons in his backyard, and it wasn't long before inspiration hit him that nature could do the same, only better. In koi, color and overall aesthetic appearance is selected for, leading over the years to the bright orange and yellow fish that swim in fancy ponds. But, just as golden retrievers were once wild wolves back along their breeding tree, so koi also have a wild origin as the common carp (Cyprinus carpio). The common carp is, well, common all throughout the rivers of Asia and Europe, and this made it easy for breeders to to their thing with it. That sounded wrong. I meant "breed" as in farm and select, not...you know...

But, just as golden retrievers were once wild wolves back along their breeding tree, so koi also have a wild origin as the common carp (Cyprinus carpio). The common carp is, well, common all throughout the rivers of Asia and Europe, and this made it easy for breeders to to their thing with it. That sounded wrong. I meant "breed" as in farm and select, not...you know...

Moving on after that long introduction (I'm hyper and I feel like a long discourse), we now arrive after years of breeding at the koi which now adorns ponds around fancy places today, and the one which I read all about. Most of this stuff is nothing too new, as I've read about fish before, but the refresh in such a tight context was interesting nonetheless. Koi are remarkably adapted to their watery home, as I learned in detail. They have exceptional eyesight, even under low light conditions. Their sense of touch is compartmentalized into a structure called the lateral line, a shallow groove which runs the length of both sides of the body. This groove is filled with tiny pores, which are in turn filled with tiny, sensitive, hair-like structures. Disturbance in the water around the fish pushes pressure waves into the pores, allowing the koi to detect even minute impulses and vibrations in a directional manner, such as the footsteps of an approaching person. They have no teeth, but instead have rings of bony plates set into the flesh of the mouth, which allow them a wide diet and versatile chewing. Koi also have a remarkable system for buoyancy, making use of a swim bladder. This is a segmented organ lying below the vertebral column, which is filled with air, transported dissolved from the gills. In response to depth, the bladder releases and takes on air, allowing the fish to move up and down in the water column. Their gills are also quite interesting, essentially serving as exposed lungs, with gases diffusing across their membranes. but in order to keep this diffusion going, the fish actually have to actively transport ions into their cells in order to maintain a concentration gradient for water levels, called osmoregulation.

Anyway, that's my fact-vomit about koi, I hope you enjoyed it =)

I have always found fish fascinating. Well, hell, I find all animals fascinating, but I suppose for simple aesthetic intrigue, the fluid movements and interesting lifestyles of aquatic animals have always been a thrill to watch or learn about. Fortunately, with the koi, I had the chance to do both. Inside the house, I was looking at books on the coffee table, and I found one all about koi. Most of it was arcane stuff on their care and maintenance, with some sections even devoted to the professional showing of koi. But there was a chapter leading up to their healthcare that discussed in pleasing detail their biology and physiology. Needless to say, I read it all, and am pleased to say I now know much more about koi fish than I did before, so let me share a brief overview of the animals for my fun fact this evening.

I have always found fish fascinating. Well, hell, I find all animals fascinating, but I suppose for simple aesthetic intrigue, the fluid movements and interesting lifestyles of aquatic animals have always been a thrill to watch or learn about. Fortunately, with the koi, I had the chance to do both. Inside the house, I was looking at books on the coffee table, and I found one all about koi. Most of it was arcane stuff on their care and maintenance, with some sections even devoted to the professional showing of koi. But there was a chapter leading up to their healthcare that discussed in pleasing detail their biology and physiology. Needless to say, I read it all, and am pleased to say I now know much more about koi fish than I did before, so let me share a brief overview of the animals for my fun fact this evening.The perhaps foremost, possibly obviously so, fact about koi is that they are not wild animals. It's impossible for one to wander off to some distant pond and find schools of koi plying the waters there, just as one wouldn't expect to find packs of golden retrievers hunting caribou in the forest. But, that being said, they are domesticated animals, and this means that they are an intriguing example of what Darwin himself drew the inspiration for his theory from: artificial selection. In this form of selection, a breeder allows only certain offspring to reproduce, those that bear the characteristics which said breeder is looking for. Instead of the most overall fit animal reproducing the most, as in natural selection (the engine of evolution), the animals bearing the most developed traits desired by the breeder are instead selected. Darwin himself did this with pigeons in his backyard, and it wasn't long before inspiration hit him that nature could do the same, only better. In koi, color and overall aesthetic appearance is selected for, leading over the years to the bright orange and yellow fish that swim in fancy ponds.

But, just as golden retrievers were once wild wolves back along their breeding tree, so koi also have a wild origin as the common carp (Cyprinus carpio). The common carp is, well, common all throughout the rivers of Asia and Europe, and this made it easy for breeders to to their thing with it. That sounded wrong. I meant "breed" as in farm and select, not...you know...

But, just as golden retrievers were once wild wolves back along their breeding tree, so koi also have a wild origin as the common carp (Cyprinus carpio). The common carp is, well, common all throughout the rivers of Asia and Europe, and this made it easy for breeders to to their thing with it. That sounded wrong. I meant "breed" as in farm and select, not...you know...Moving on after that long introduction (I'm hyper and I feel like a long discourse), we now arrive after years of breeding at the koi which now adorns ponds around fancy places today, and the one which I read all about. Most of this stuff is nothing too new, as I've read about fish before, but the refresh in such a tight context was interesting nonetheless. Koi are remarkably adapted to their watery home, as I learned in detail. They have exceptional eyesight, even under low light conditions. Their sense of touch is compartmentalized into a structure called the lateral line, a shallow groove which runs the length of both sides of the body. This groove is filled with tiny pores, which are in turn filled with tiny, sensitive, hair-like structures. Disturbance in the water around the fish pushes pressure waves into the pores, allowing the koi to detect even minute impulses and vibrations in a directional manner, such as the footsteps of an approaching person. They have no teeth, but instead have rings of bony plates set into the flesh of the mouth, which allow them a wide diet and versatile chewing. Koi also have a remarkable system for buoyancy, making use of a swim bladder. This is a segmented organ lying below the vertebral column, which is filled with air, transported dissolved from the gills. In response to depth, the bladder releases and takes on air, allowing the fish to move up and down in the water column. Their gills are also quite interesting, essentially serving as exposed lungs, with gases diffusing across their membranes. but in order to keep this diffusion going, the fish actually have to actively transport ions into their cells in order to maintain a concentration gradient for water levels, called osmoregulation.

Anyway, that's my fact-vomit about koi, I hope you enjoyed it =)

"Inception"

I usually don't post about the menial events that make up my every day life, but if something comes along worth some interest, I'll definitely share it.  And so I figured I'd share one interesting part of my day today: I saw "Inception", the new directorial effort by Christopher Nolan (who, might I add, also directed "The Dark Knight", the best Batman movie ever). And let me just say this: it was awesome. Seriously, go see this movie if you get the chance. I won't give away the plot, but let me just say that the ending will have you thinking for quite some time. Totally worth $9. Honestly.

And so I figured I'd share one interesting part of my day today: I saw "Inception", the new directorial effort by Christopher Nolan (who, might I add, also directed "The Dark Knight", the best Batman movie ever). And let me just say this: it was awesome. Seriously, go see this movie if you get the chance. I won't give away the plot, but let me just say that the ending will have you thinking for quite some time. Totally worth $9. Honestly.

And so I figured I'd share one interesting part of my day today: I saw "Inception", the new directorial effort by Christopher Nolan (who, might I add, also directed "The Dark Knight", the best Batman movie ever). And let me just say this: it was awesome. Seriously, go see this movie if you get the chance. I won't give away the plot, but let me just say that the ending will have you thinking for quite some time. Totally worth $9. Honestly.

And so I figured I'd share one interesting part of my day today: I saw "Inception", the new directorial effort by Christopher Nolan (who, might I add, also directed "The Dark Knight", the best Batman movie ever). And let me just say this: it was awesome. Seriously, go see this movie if you get the chance. I won't give away the plot, but let me just say that the ending will have you thinking for quite some time. Totally worth $9. Honestly.

Thursday, July 15, 2010

Fun Fact of the Day 7/15

Hello all, so sorry about my week of inactivity, I just have been starting posts and never finishing them, and this has led to several days of, well, nothing. And I feel bad! So, let me at least post a fun fact this evening to make up for it.

Well, a few minutes ago, I was walking home and I had to navigate through my backyard in order to get a spare key. I was with friends, and I told them to watch for black widow spiders along the way, since we have alot in my backyard. Then I ended up explaining the stages of symptoms one would display if bitten by a female black widow. That got me thinking about venoms and whatnot, and so I figured I'd talk about something of the sort for this post.

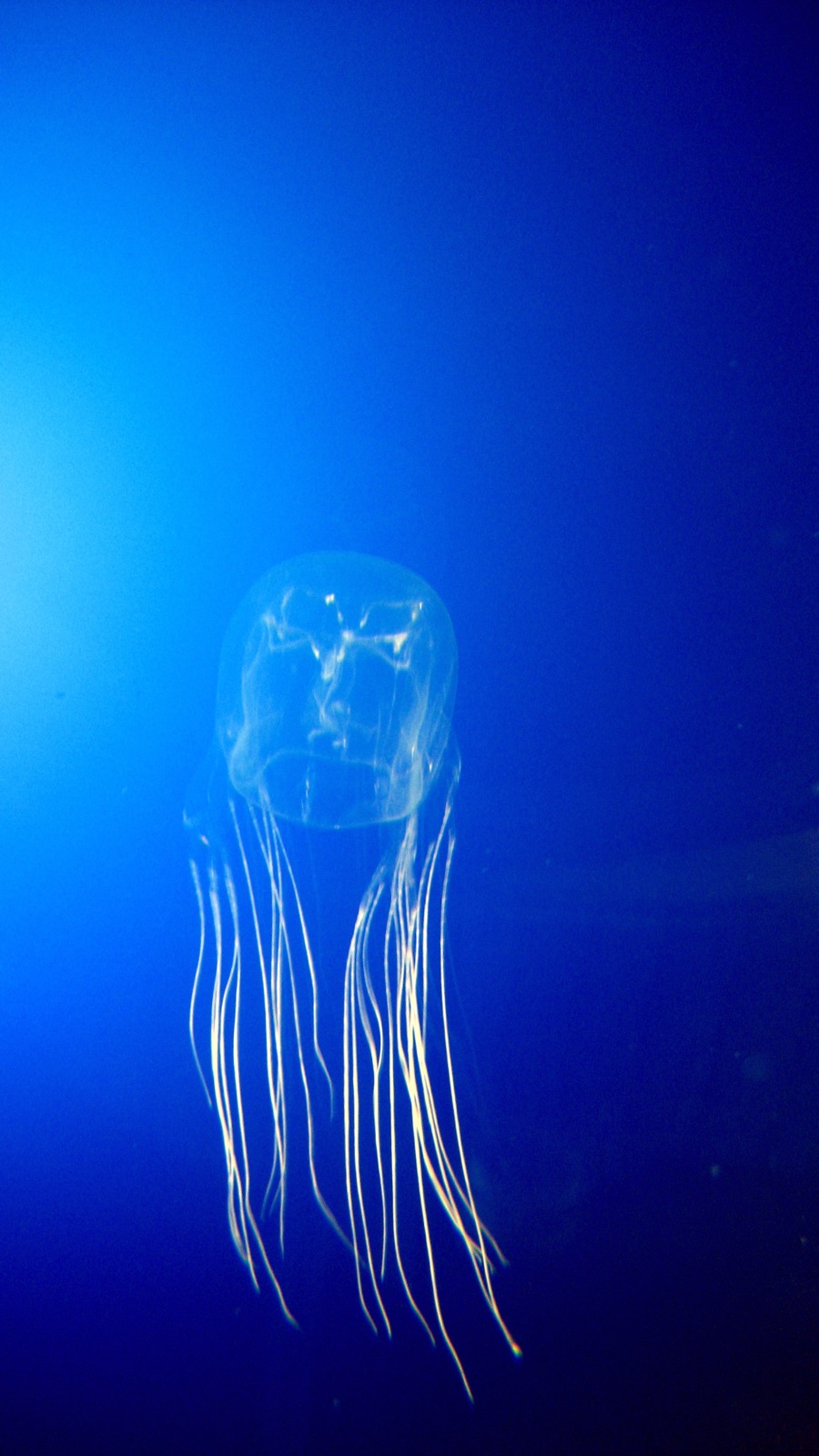

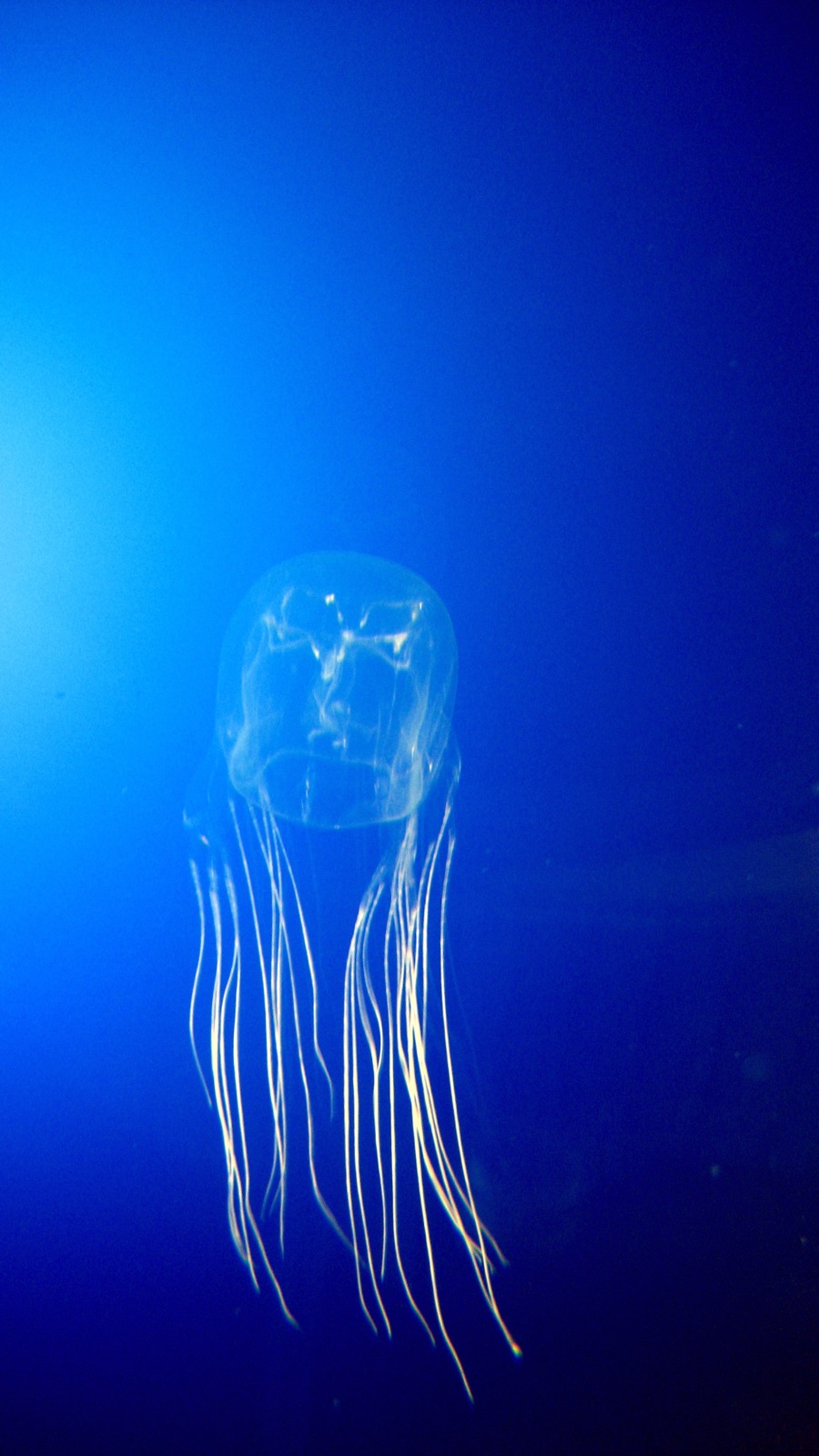

Now, it's difficult to quantify what would qualify as the most venomous animal on earth, because of the variance in animals with venom. Some have highly toxic venom but deliver it in small amounts. Some is more corrosive, but less toxic. Others are less likely to bite or sting, and so on and so forth. But if one were to look into it, almost all sources would pinpoint the title of "most venomous" as belonging to Australia's Box jellyfish, members of the class Cubozoa. Of this class, only a few species are truly dangerous, the most common of which is the so-called "sea wasp", Chironex fleckeri. Also extremely dangerous is the tiny Irukandji jellyfish, of which there are two species.

members of the class Cubozoa. Of this class, only a few species are truly dangerous, the most common of which is the so-called "sea wasp", Chironex fleckeri. Also extremely dangerous is the tiny Irukandji jellyfish, of which there are two species.

The venom of these species is legendary for it's lethality, and in places such as the Philippines, 20-40 people die annually from stings. It is rumored that a sting from one of these species of box jellyfish can kill a person within five minutes and indeed, it is speculated that the chances of survival if stung while swimming alone are "near zero". But how exactly, the inquisitive among you may ask, does this venom work? Well, to understand this, you have to understand the process of injection on a cellular level, which is really quite fascinating when you get right down to it. See, cnidarians (a phylum of animals that includes jellyfish) often use venom of varying toxicity as a means of defense or to subdue prey. To utilize these toxins, they must have a means of actually injecting them into prey. And with the absence of jaws or any other sting or fang-bearing parts, cnidarians instead use specialized cells called cnidocytes, also known as nematocytes.

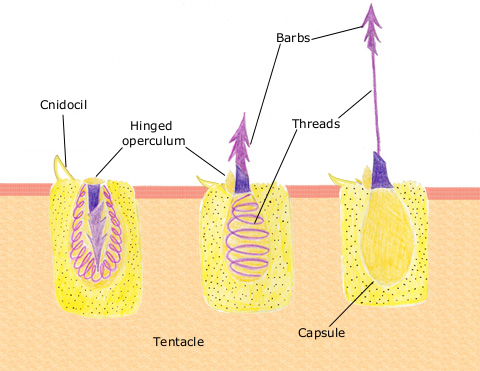

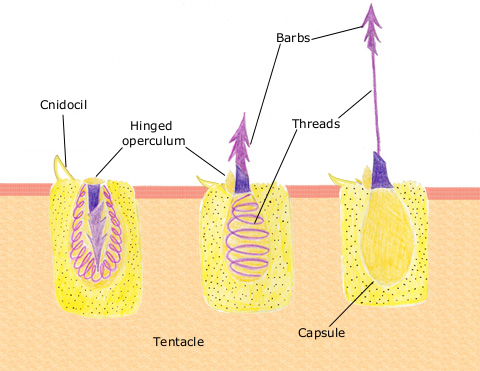

And with the absence of jaws or any other sting or fang-bearing parts, cnidarians instead use specialized cells called cnidocytes, also known as nematocytes.  The purpose of these cells is to detect contact with the tentacle or skin and inject venom upon contact. To do so, they contain organelles within the cell called nematocysts. Each nematocyst is a bulblike structure surrounded by a coiled tube structure. There is a hair-like trigger on the external part of the cell called a cnidocil. When the cnidocil is activated, it causes the release of calcium ions from the inside of the coiled nematocyst. The result is a rapid influx of water into the cell itself from the outside, creating osmotic pressure which then forces the coiled nematocyst our of the cell, with water righting the needle-like center and forcing it into the target organism. The bulb contains venom, which is then injected. Several thousand or more of these cells fire their toxic payloads within nanoseconds, making them one of the fastest reactions in the animal kingdom with an acceleration of over 5 million Gs. Fascinating, isn't it?!

The purpose of these cells is to detect contact with the tentacle or skin and inject venom upon contact. To do so, they contain organelles within the cell called nematocysts. Each nematocyst is a bulblike structure surrounded by a coiled tube structure. There is a hair-like trigger on the external part of the cell called a cnidocil. When the cnidocil is activated, it causes the release of calcium ions from the inside of the coiled nematocyst. The result is a rapid influx of water into the cell itself from the outside, creating osmotic pressure which then forces the coiled nematocyst our of the cell, with water righting the needle-like center and forcing it into the target organism. The bulb contains venom, which is then injected. Several thousand or more of these cells fire their toxic payloads within nanoseconds, making them one of the fastest reactions in the animal kingdom with an acceleration of over 5 million Gs. Fascinating, isn't it?!

So, hopefully this interesting fact makes up for my inability to complete composed posts, but not to worry, I'll get back into the regular swing of things. Thanks for reading, and swim safely...

Well, a few minutes ago, I was walking home and I had to navigate through my backyard in order to get a spare key. I was with friends, and I told them to watch for black widow spiders along the way, since we have alot in my backyard. Then I ended up explaining the stages of symptoms one would display if bitten by a female black widow. That got me thinking about venoms and whatnot, and so I figured I'd talk about something of the sort for this post.

Now, it's difficult to quantify what would qualify as the most venomous animal on earth, because of the variance in animals with venom. Some have highly toxic venom but deliver it in small amounts. Some is more corrosive, but less toxic. Others are less likely to bite or sting, and so on and so forth. But if one were to look into it, almost all sources would pinpoint the title of "most venomous" as belonging to Australia's Box jellyfish,

members of the class Cubozoa. Of this class, only a few species are truly dangerous, the most common of which is the so-called "sea wasp", Chironex fleckeri. Also extremely dangerous is the tiny Irukandji jellyfish, of which there are two species.

members of the class Cubozoa. Of this class, only a few species are truly dangerous, the most common of which is the so-called "sea wasp", Chironex fleckeri. Also extremely dangerous is the tiny Irukandji jellyfish, of which there are two species.The venom of these species is legendary for it's lethality, and in places such as the Philippines, 20-40 people die annually from stings. It is rumored that a sting from one of these species of box jellyfish can kill a person within five minutes and indeed, it is speculated that the chances of survival if stung while swimming alone are "near zero". But how exactly, the inquisitive among you may ask, does this venom work? Well, to understand this, you have to understand the process of injection on a cellular level, which is really quite fascinating when you get right down to it. See, cnidarians (a phylum of animals that includes jellyfish) often use venom of varying toxicity as a means of defense or to subdue prey. To utilize these toxins, they must have a means of actually injecting them into prey.

And with the absence of jaws or any other sting or fang-bearing parts, cnidarians instead use specialized cells called cnidocytes, also known as nematocytes.

And with the absence of jaws or any other sting or fang-bearing parts, cnidarians instead use specialized cells called cnidocytes, also known as nematocytes.  The purpose of these cells is to detect contact with the tentacle or skin and inject venom upon contact. To do so, they contain organelles within the cell called nematocysts. Each nematocyst is a bulblike structure surrounded by a coiled tube structure. There is a hair-like trigger on the external part of the cell called a cnidocil. When the cnidocil is activated, it causes the release of calcium ions from the inside of the coiled nematocyst. The result is a rapid influx of water into the cell itself from the outside, creating osmotic pressure which then forces the coiled nematocyst our of the cell, with water righting the needle-like center and forcing it into the target organism. The bulb contains venom, which is then injected. Several thousand or more of these cells fire their toxic payloads within nanoseconds, making them one of the fastest reactions in the animal kingdom with an acceleration of over 5 million Gs. Fascinating, isn't it?!

The purpose of these cells is to detect contact with the tentacle or skin and inject venom upon contact. To do so, they contain organelles within the cell called nematocysts. Each nematocyst is a bulblike structure surrounded by a coiled tube structure. There is a hair-like trigger on the external part of the cell called a cnidocil. When the cnidocil is activated, it causes the release of calcium ions from the inside of the coiled nematocyst. The result is a rapid influx of water into the cell itself from the outside, creating osmotic pressure which then forces the coiled nematocyst our of the cell, with water righting the needle-like center and forcing it into the target organism. The bulb contains venom, which is then injected. Several thousand or more of these cells fire their toxic payloads within nanoseconds, making them one of the fastest reactions in the animal kingdom with an acceleration of over 5 million Gs. Fascinating, isn't it?!So, hopefully this interesting fact makes up for my inability to complete composed posts, but not to worry, I'll get back into the regular swing of things. Thanks for reading, and swim safely...

Thursday, July 8, 2010

Pay Attention, Nick Fedorko

Well, I've been posting alot today, mainly to account for the periods of inactivity over the last couple of weeks, but also because there's been alot of cool news to catch up on as well.  And the latest piece of news I'll share is concerning that animal which I so often dub Nicholas Fedorko: the whale (It's a running joke, Nick's as fit as an Olympic athlete, but I always call him fat for giggles sake). This particular story concerns an ancient whale, however, and an awesome one at that. It's a species called Leviathan melvillei, a species named for "Moby Dick" author Herman Melville. And the name is entirely fitting as well. Measuring around 60 feet in length, with teeth more than a

And the latest piece of news I'll share is concerning that animal which I so often dub Nicholas Fedorko: the whale (It's a running joke, Nick's as fit as an Olympic athlete, but I always call him fat for giggles sake). This particular story concerns an ancient whale, however, and an awesome one at that. It's a species called Leviathan melvillei, a species named for "Moby Dick" author Herman Melville. And the name is entirely fitting as well. Measuring around 60 feet in length, with teeth more than a foot long, this whale was likely an extremely powerful predator when it lived in the seas of Peru 13 million years ago. As seen at right, the scientists who discovered Leviathan believe that the prehistoric whale (which was closely related to modern sperm whales) likely preyed on smaller baleen whales. In short, this animal was really awesome, and if you want some more pictures, read all about it here.

foot long, this whale was likely an extremely powerful predator when it lived in the seas of Peru 13 million years ago. As seen at right, the scientists who discovered Leviathan believe that the prehistoric whale (which was closely related to modern sperm whales) likely preyed on smaller baleen whales. In short, this animal was really awesome, and if you want some more pictures, read all about it here.

And the latest piece of news I'll share is concerning that animal which I so often dub Nicholas Fedorko: the whale (It's a running joke, Nick's as fit as an Olympic athlete, but I always call him fat for giggles sake). This particular story concerns an ancient whale, however, and an awesome one at that. It's a species called Leviathan melvillei, a species named for "Moby Dick" author Herman Melville. And the name is entirely fitting as well. Measuring around 60 feet in length, with teeth more than a

And the latest piece of news I'll share is concerning that animal which I so often dub Nicholas Fedorko: the whale (It's a running joke, Nick's as fit as an Olympic athlete, but I always call him fat for giggles sake). This particular story concerns an ancient whale, however, and an awesome one at that. It's a species called Leviathan melvillei, a species named for "Moby Dick" author Herman Melville. And the name is entirely fitting as well. Measuring around 60 feet in length, with teeth more than a foot long, this whale was likely an extremely powerful predator when it lived in the seas of Peru 13 million years ago. As seen at right, the scientists who discovered Leviathan believe that the prehistoric whale (which was closely related to modern sperm whales) likely preyed on smaller baleen whales. In short, this animal was really awesome, and if you want some more pictures, read all about it here.

foot long, this whale was likely an extremely powerful predator when it lived in the seas of Peru 13 million years ago. As seen at right, the scientists who discovered Leviathan believe that the prehistoric whale (which was closely related to modern sperm whales) likely preyed on smaller baleen whales. In short, this animal was really awesome, and if you want some more pictures, read all about it here.Super Strength Smilodon

Smilodon is an animal you may better know by it's colloquial name, the "saber-toothed tiger".  These animals lived in the Pleistocene epoch, from around 1.8 million years ago to ten thousand years ago, and inhabited both North and South America. Anyone who has been to the La Brea Tar Pits (lucky people, I still haven't been there) has likely seen the skeleton of one of these imposing felines, most notably their enormous front fangs, which could reach around 11 inches in length. Despite their large size, these canines were actually rather weak, and in a new study published last week, it was revealed that these teeth required assistance in their function from other parts of the body. See, most modern feline teeth have conical cores, providing them with a great deal of strength against the stresses they encounter during biting and piercing. Smilodon, however, had oval-shaped teeth, and this made them more vulnerable to breaking during use.

These animals lived in the Pleistocene epoch, from around 1.8 million years ago to ten thousand years ago, and inhabited both North and South America. Anyone who has been to the La Brea Tar Pits (lucky people, I still haven't been there) has likely seen the skeleton of one of these imposing felines, most notably their enormous front fangs, which could reach around 11 inches in length. Despite their large size, these canines were actually rather weak, and in a new study published last week, it was revealed that these teeth required assistance in their function from other parts of the body. See, most modern feline teeth have conical cores, providing them with a great deal of strength against the stresses they encounter during biting and piercing. Smilodon, however, had oval-shaped teeth, and this made them more vulnerable to breaking during use.  Additionally, Smilodon's jaws had smaller zygomatic arches, which reduce the thickness of the temporalis muscles, and thus reduce the available bite force.

Additionally, Smilodon's jaws had smaller zygomatic arches, which reduce the thickness of the temporalis muscles, and thus reduce the available bite force.

But in the study, scientists have discovered that this was not a huge problem for Smilodon, as it had immensely powerful front limbs to account for this. The study plotted the rigidity and strength of the arm bones of Smilodon against several other species, and it was revealed that the comparative strength of these was remarkably powerful. They had thicker forelimbs and thicker cortical bone, which would have allowed the animal a great deal more flexing power with the front limbs. This means that, despite it's decreased ability to use it's bite as a weapon, Smilodon could have easily wrestled prey to the ground with it's beefy arms, and then let the jaws finish the prey off.

the rigidity and strength of the arm bones of Smilodon against several other species, and it was revealed that the comparative strength of these was remarkably powerful. They had thicker forelimbs and thicker cortical bone, which would have allowed the animal a great deal more flexing power with the front limbs. This means that, despite it's decreased ability to use it's bite as a weapon, Smilodon could have easily wrestled prey to the ground with it's beefy arms, and then let the jaws finish the prey off.

Just goes to show, evolution is a much better body-builder than any human being. (Especially me, I tried doing pull-ups this morning, and I could barely finish two of them before my arms just about exploded...)

These animals lived in the Pleistocene epoch, from around 1.8 million years ago to ten thousand years ago, and inhabited both North and South America. Anyone who has been to the La Brea Tar Pits (lucky people, I still haven't been there) has likely seen the skeleton of one of these imposing felines, most notably their enormous front fangs, which could reach around 11 inches in length. Despite their large size, these canines were actually rather weak, and in a new study published last week, it was revealed that these teeth required assistance in their function from other parts of the body. See, most modern feline teeth have conical cores, providing them with a great deal of strength against the stresses they encounter during biting and piercing. Smilodon, however, had oval-shaped teeth, and this made them more vulnerable to breaking during use.

These animals lived in the Pleistocene epoch, from around 1.8 million years ago to ten thousand years ago, and inhabited both North and South America. Anyone who has been to the La Brea Tar Pits (lucky people, I still haven't been there) has likely seen the skeleton of one of these imposing felines, most notably their enormous front fangs, which could reach around 11 inches in length. Despite their large size, these canines were actually rather weak, and in a new study published last week, it was revealed that these teeth required assistance in their function from other parts of the body. See, most modern feline teeth have conical cores, providing them with a great deal of strength against the stresses they encounter during biting and piercing. Smilodon, however, had oval-shaped teeth, and this made them more vulnerable to breaking during use.  Additionally, Smilodon's jaws had smaller zygomatic arches, which reduce the thickness of the temporalis muscles, and thus reduce the available bite force.

Additionally, Smilodon's jaws had smaller zygomatic arches, which reduce the thickness of the temporalis muscles, and thus reduce the available bite force.But in the study, scientists have discovered that this was not a huge problem for Smilodon, as it had immensely powerful front limbs to account for this. The study plotted

the rigidity and strength of the arm bones of Smilodon against several other species, and it was revealed that the comparative strength of these was remarkably powerful. They had thicker forelimbs and thicker cortical bone, which would have allowed the animal a great deal more flexing power with the front limbs. This means that, despite it's decreased ability to use it's bite as a weapon, Smilodon could have easily wrestled prey to the ground with it's beefy arms, and then let the jaws finish the prey off.

the rigidity and strength of the arm bones of Smilodon against several other species, and it was revealed that the comparative strength of these was remarkably powerful. They had thicker forelimbs and thicker cortical bone, which would have allowed the animal a great deal more flexing power with the front limbs. This means that, despite it's decreased ability to use it's bite as a weapon, Smilodon could have easily wrestled prey to the ground with it's beefy arms, and then let the jaws finish the prey off.Just goes to show, evolution is a much better body-builder than any human being. (Especially me, I tried doing pull-ups this morning, and I could barely finish two of them before my arms just about exploded...)

Vampires!

So I saw "Eclipse" yesterday...no, don't get me wrong, I'm not a Twilight fan, but it was something to do and I have a running joke about having a crush on Edward, so it was obligatory to see the movie. It was pretty corny, I'll say that much, but that's to be expected. But what always gets me further is the fact that the science in these movies is horrendous. I mean, yes, they're not supposed to be realistic, but the anatomical constraints of transforming into a giant wolf in under a second are...ridiculous. At any rate, I figured I'd at least interject a little bit of science into the whole affair, with this paper I read a couple of months ago by population ecology graduate student: Enjoy!

Wednesday, July 7, 2010

Fun Fact of the Day 7/7

So, while up in San Luis Obispo, I went with my aunt, uncle, and cousin, to one of my favorite places on the central coast: the Piedras Blancas elephant seal colony. So, I figured I'd share some basic information on elephant seals, because they're pretty awesome.

So, while up in San Luis Obispo, I went with my aunt, uncle, and cousin, to one of my favorite places on the central coast: the Piedras Blancas elephant seal colony. So, I figured I'd share some basic information on elephant seals, because they're pretty awesome.First off, there are two species of elephant seals: northern and southern. The southern species is larger, and is in fact larger than all other pinnipeds, and dwells south of the equator, usually in sub-antarctic waters. The northern species (Mirounga angustirostris), while smaller, is no dwarf, especially by seal standards.

They can reach around 14 feet in length and weigh over 5,000 pounds, at least in the larger males. Elephant seals display what is called sexual dimorphism, wherein the males and females differ anatomically from one another. Elephant seal males are much larger, and they bear an enormous nose, which gives the species it's name. Females are smaller, and lack the large nose, looking more like normal seals. If you look at the above image, a female is pictured on the left, a male on the right.

They can reach around 14 feet in length and weigh over 5,000 pounds, at least in the larger males. Elephant seals display what is called sexual dimorphism, wherein the males and females differ anatomically from one another. Elephant seal males are much larger, and they bear an enormous nose, which gives the species it's name. Females are smaller, and lack the large nose, looking more like normal seals. If you look at the above image, a female is pictured on the left, a male on the right.Elephant seals also have a remarkable yearly behavior cycle. When at sea, they spend a large amount of time underwater, and can dive to incredible depths to hunt squid, often in excess of 1,000 feet below the surface. To aid in this, the seals have specially adapted blood vessels which store carbon dioxide, allowing them to not become poisoned by it, and then expelling it upon surfacing. Their breeding cycle is one of two events that brings them to land. In late fall, males will first hit the beach, and immediately begin to establish territory by fighting with other males over space.

These fights can be very violent, and males usually have a large amount of scar tissue on their chests from such encounters (I personally saw one when I was around 7 that drew a huge amount of blood, with one male eventually fleeing, bloody, into the surf). Later in the winter, around December, the females then come ashore. It is at this point that the previously established space becomes important, as each female soon settles into a particular area around a male, forming groups of "harems" for each male. The females then give birth, and spend the next few weeks nursing their pup on extremely rich milk, promoting rapid growth. Then comes weaning, in which (sadly) the female will then mate with the nearby male and head out to sea. She may have lost nearly a third of her body weight by this time from nursing, as she does not eat on land at all, and she immediately feeds. The pups are left on the beach to figure it all out, and will eventually enter the ocean themselves, though some linger until spring. The males also depart to feed after mating, and the breeding season ends. They also come back in the summer to molt, which is what I saw this past monday, with the males arriving and shedding first, and the females in late summer.

These fights can be very violent, and males usually have a large amount of scar tissue on their chests from such encounters (I personally saw one when I was around 7 that drew a huge amount of blood, with one male eventually fleeing, bloody, into the surf). Later in the winter, around December, the females then come ashore. It is at this point that the previously established space becomes important, as each female soon settles into a particular area around a male, forming groups of "harems" for each male. The females then give birth, and spend the next few weeks nursing their pup on extremely rich milk, promoting rapid growth. Then comes weaning, in which (sadly) the female will then mate with the nearby male and head out to sea. She may have lost nearly a third of her body weight by this time from nursing, as she does not eat on land at all, and she immediately feeds. The pups are left on the beach to figure it all out, and will eventually enter the ocean themselves, though some linger until spring. The males also depart to feed after mating, and the breeding season ends. They also come back in the summer to molt, which is what I saw this past monday, with the males arriving and shedding first, and the females in late summer.  So, there you have it, these are cool animals, and you should really go check them out if you're ever near Cambria or Hearst Castle.

So, there you have it, these are cool animals, and you should really go check them out if you're ever near Cambria or Hearst Castle.

Monday, July 5, 2010

Hark! I Have News! And Excuses.

Hello, all. Sorry for the lack of fun facts the past two days, but I'm once again on the go, this time visiting my cousin in Templeton, near San Luis Obispo. If I can, I'll share a fun fact later, but we've been pretty busy up here, so it's unlikely.

In other news, I was extremely excited two nights ago when I got an email from the professor I volunteered for earlier this summer studying ground squirrels. In short, she offered me a job! =D Yep, one of their employees bailed for a job in Wyoming, and they're now short-staffed, so she offered for me to go back up there and do more research work. I'm going to try and do it, for sure, but I'd figured I'd share since I was excited.

In other news, I was extremely excited two nights ago when I got an email from the professor I volunteered for earlier this summer studying ground squirrels. In short, she offered me a job! =D Yep, one of their employees bailed for a job in Wyoming, and they're now short-staffed, so she offered for me to go back up there and do more research work. I'm going to try and do it, for sure, but I'd figured I'd share since I was excited.

Friday, July 2, 2010

Fun Facts to Start July: Stream of Consciousness Again

Well, I figured, since I didn't post at all yesterday, that I'd do another "stream of consciousness" style fun fact pack for this evening. So, let's get started shall we?

- Elephants (the new title picture, like it?) often are major factors in open woodland environments in Africa because of their tendency to topple trees to get at the tasty leaves at the top. Giraffes evolved the neck, elephants just knock the whole affair down.

- Sperm whales are well known for hunting squid, some of their favorite prey. To do so, they dive to enormous and highly pressurized depths, and use sonar to find prey while holding their breath, sometimes for more than two hours. But one remarkable adaptation they are believed to have is the ability to focus the sound that they use in such a concentrated manner that they can use it to stun nearby squid.

- "Daddy-long legs" are not actually spiders. They are members of the order Opiliones, while spiders are in the order Araneae. Opliliones contains over 6,400 species, all known as harvestmen.

- There once was an enormous varanid (monitor lizards and their kin, including Komodo Dragons) known as Megalania, which lived in Australia after the last ice age. Fossils indicate that the animal grew over 20 feet long, making the largest known lizard in history

- According to a recent calculation, social insects alone (ants, bees, and some wasps) actually equal or perhaps exceed the biomass of humans on the planet.

- Sharks do not get cancer

- Most owls keenest sense is hearing, and some, such as the widespread Barn owl (Tyto alba) can hear the heartbeat of a mouse from 40 feet in the air

- Polar bears are known to hunt seal breathing holes in the polar ice, even punching their own and waiting for unwary mammals to surface. They wait by the holes laying down in the snow, and some actually cover their noses for complete camoflauge, since their nose is the darkest part of their face

- an octopus 15 feet across can fit through a space the size of a quarter

- The archerfish of Southeast asia has a groove on the roof of it's mouth that it uses to squirt water upwards with it's tongue, shooting insects off of overhanging branches to eat

- Pterodactyl is not a defined species, bu rather refers to the group (pterosaurs as a whole). The most typified image of a "pterodactyl" is a species called Pteranodon. They were also not dinosaurs, but flying reptiles.

- Sandtiger Sharks (also known as Grey Nurse and Raggedtooth Sharks in Australia and South Africa, respectively) have young that develop live in the womb. It is common for one baby, larger than the rest, to eat many of it's siblings while still inside the mother

- Badgers are rumored to be able to dig so fast, they appear to sink into the ground in a spray of dirt. This is due to their large digging claws and strong muscles, which assist them in digging, both for shelter and for prey

- The largest frog in the world is the african Goliath Frog, which can be nearly three feet long

- The evolution of color vision was driven largely by the need to differentiate between poisonous and non-poisonous plants for food

- Whale baleen, used to strain plankton in many species, is made out of the same material as fingernails, a protein called keratin

- Wolverines, the largest mustelid in the world, are said to be able to kill and eat snowbound moose in the winter, despite being barely the size of a small dog

- The average shrew must eat 80-90% of it's own weight in food every day in order to stay alive with it's breakneck metabolism

- Beavers' teeth never stop growing, they are constantly worn down by the tree-chewing habits of the animal, as well as it's diet of bark

- A cougar can jump nearly 20 feet straight into the air from a standing position

- Batman is much better than Superman

New Design

Well, I set out yesterday to plug in a new header picture for the month of July, but I ended up re-designing the format of the whole blog. I've been continually tampering with it today as well, so there might be more tinkering in the future. Over all though, I'm pretty happy with how it looks. Hopefully you all are too!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)